Reviewed 2012

What is the PPP site?

We developed the Plants, Pathogens, and People (PPP) web site to increase students’ understanding of agriculture and science-related topics. On our site, plant disease epidemics are used as case studies to illustrate important science and societal issues related to agriculture. Depending on the intent of the instructors who use the materials, the focus can be on the issues and how they pertain to a particular field of study (e.g. biology, history, or health) or on the agricultural system itself. The site helps students to develop a better understanding of the scientific process and methods of experimentation. Currently students can explore the topics of late blight and the Irish potato famine, Dutch elm disease and the decline of the American elm, and crown gall and genetic modification of plants. Additional case studies will be added in the future.

students’ understanding of agriculture and science-related topics. On our site, plant disease epidemics are used as case studies to illustrate important science and societal issues related to agriculture. Depending on the intent of the instructors who use the materials, the focus can be on the issues and how they pertain to a particular field of study (e.g. biology, history, or health) or on the agricultural system itself. The site helps students to develop a better understanding of the scientific process and methods of experimentation. Currently students can explore the topics of late blight and the Irish potato famine, Dutch elm disease and the decline of the American elm, and crown gall and genetic modification of plants. Additional case studies will be added in the future.

Why did we create the PPP site?

Scientifically aware people use scientific knowledge and scientific ways of thinking to help them make decisions and to better understand many of the problems they deal with every day (Rutherford and Ahlgren, 1990). Similarly, agriculturally aware people use these same ways of thinking and knowledge of the agricultural system when dealing with issues related to agriculture. Unfortunately, a large percentage of college undergraduates do not understand the modern agricultural system or its impact on them. The PPP site was designed to help undergraduate students become more aware of some of the important topics and questions in today’s agriculture. The development of genetically modified organisms, the use of pesticides, and the preservation of genetic diversity and of the environment are some of the issues about which all students need to be informed if they are to become truly educated citizens. The web site uses examples from the field of plant pathology to explore such subjects and to show how they impact society as a whole.

We initially created the PPP site for use by students in our general education plant pathology course at the University of Illinois (Schumann and D’Arcy, 1999). Plant Pathology 100 fulfills campus requirements in both natural science and composition. Enrollment is capped at 75 students, and the course has been fully enrolled every semester it has been offered since 1993.

We realized that our 75 students could represent every possible learning style, and would learn best with different methods of instruction. Therefore, our goal was to provide information in a variety of formats. Because there are few available teaching resources for a course on the societal impacts of plant diseases, we decided to create our own instruction aids. Initially, we produced two videotape presentations currently available from APS Press, one on late blight and the Irish potato famine (Eastburn and D’Arcy, 1996) and a second on the impact of Dutch elm disease on the American elm (Eastburn et al., 2000). The videos were designed to supplement information presented in lecture.

In response to a grant proposal that we submitted to obtain  funding for additional video projects, the grant review panel encouraged us to consider developing instructional materials that would promote active learning and foster inquiry-based forms of instruction. Inquiry-based techniques encourage students develop a line of inquiry that makes sense to them and enhances learning by allowing them to explore the aspects in which they are most interested (Benson and Bruce, 2001). Computer-based media seemed like they would be an effective way to provide such materials, and we briefly considered developing a program that would be distributed in CD-ROM format. However, this was about the same time that the capabilities of the internet were improving dramatically, and the use of the world wide web was being explored as an educational tool. The format of the web offers some unique possibilities for presenting instructional material (Burbules and Callister, 2000). We were attracted by the notion of developing a web site that would be more than an on-line repository of the course syllabus, notes, and exams. Having course material on the web would allow students to explore information at their own pace and to obtain more detail on aspects of most interest to them, a key aspect of inquiry-based learning. Providing information on the web also would allow us to accommodate a diversity of student learning styles by presenting information in several different formats, including text, images, and interactive activities. In addition, the web format would allow us to develop virtual laboratory exercises which would familiarize students with the processes of experimentation and the scientific method, while reinforcing the concepts we want them to learn. Our primary goal in the development of the PPP site is to engage students more actively in the learning process.

funding for additional video projects, the grant review panel encouraged us to consider developing instructional materials that would promote active learning and foster inquiry-based forms of instruction. Inquiry-based techniques encourage students develop a line of inquiry that makes sense to them and enhances learning by allowing them to explore the aspects in which they are most interested (Benson and Bruce, 2001). Computer-based media seemed like they would be an effective way to provide such materials, and we briefly considered developing a program that would be distributed in CD-ROM format. However, this was about the same time that the capabilities of the internet were improving dramatically, and the use of the world wide web was being explored as an educational tool. The format of the web offers some unique possibilities for presenting instructional material (Burbules and Callister, 2000). We were attracted by the notion of developing a web site that would be more than an on-line repository of the course syllabus, notes, and exams. Having course material on the web would allow students to explore information at their own pace and to obtain more detail on aspects of most interest to them, a key aspect of inquiry-based learning. Providing information on the web also would allow us to accommodate a diversity of student learning styles by presenting information in several different formats, including text, images, and interactive activities. In addition, the web format would allow us to develop virtual laboratory exercises which would familiarize students with the processes of experimentation and the scientific method, while reinforcing the concepts we want them to learn. Our primary goal in the development of the PPP site is to engage students more actively in the learning process.

What is on the PPP site?

Material on the PPP site is presented as a series of questions to foster inquiry-based learning. In the Resources and Activities, students are invited to explore areas of interest to them, including the history and economic impact of plant disease epidemics, the importance of plants, the biology of plant pathogens, the effects of environment and vectors on disease development, and the management of plant diseases. Currently, questions on the site are related to three case studies: late blight and the Irish potato famine, Dutch elm disease and the American elm, and crown gall and genetic modification.

For each case study, the student can explore text and image Resources on the topic, and can do virtual experimental Activities. The first module addresses issues of both biology and politics through the case of late blight and the Irish potato famine. The late blight epidemic of the mid-1840s resulted in the starvation and forced emigration of millions of Irish. The Resources segments include information on the history of the potato, the social conditions in Ireland in the 1840s, the biology of the late blight pathogen, and the concept of the plant disease triangle. The Activities allow students to evaluate the effects of temperature, rainfall, resistant varieties, and fungicides on the development of late blight. As for all Activities on the site, students record their hypotheses, observations, and conclusions in a lab notebook that can be emailed to their instructor when completed. They also can take a quiz to test their understanding of the topic.

record their hypotheses, observations, and conclusions in a lab notebook that can be emailed to their instructor when completed. They also can take a quiz to test their understanding of the topic.

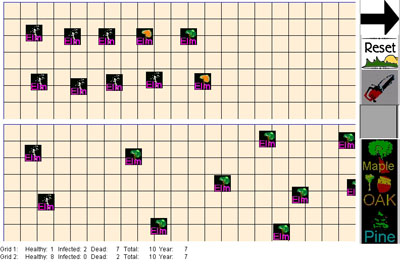

A second module on the site addresses the advantages and disadvantages of plant monocultures through the example of the continuing epidemic of Dutch elm disease in the U.S.A. The Resources include information on the appearance of the disease in Europe and its dissemination to the U.S.A., the early research on the disease by Dutch women plant pathologists, the role of insect vectors in disease transmission, and the strategies for disease management. In the Activities students can evaluate the effects of plant spacing, mixed stands vs. monocultures, and sanitation practices on disease progression over time.

A third module, currently in development, uses crown gall to explore the issue of genetic modification of plants by people. The history of plant improvement, the role of Agrobacterium tumefaciens in crown gall and in genetic modification of plants, and the benefits and problems of genetic modification are discussed in the Resources section. Student Activities will include an animated demonstration of how transgenic plants are created, as well as interactive exercises on screening transgenic plants for monogenic and polygenic host resistance and on the development of strains of pathogens with the ability to overcome host resistance in transgenic plants.

The site is structured to allow students to pursue the avenues that are most interesting to them at their own pace. Information is presented in several different formats, including photographs, micrographs, maps, audio files, and written text. In the future, we plan to add more audio and short video segments. Some of the materials (photographs, micrographs, maps) can be accessed through Tools, as can a dictionary and a calculator. The site also contains a Library with links to related web sites and citations for other reference materials.

The Dialogue section of the site provides students and teachers an opportunity to engage in a conversation with others about agricultural science. Students can discuss what they are learning and can collaborate as they investigate problems. Instructors can discuss and collaborate, as well, and they can share curriculum ideas and approaches to teaching. Any user can complete a site evaluation to provide us with information on how to make the site more effective, or can collaborate to improve the site by sending material to be posted.

the site provides students and teachers an opportunity to engage in a conversation with others about agricultural science. Students can discuss what they are learning and can collaborate as they investigate problems. Instructors can discuss and collaborate, as well, and they can share curriculum ideas and approaches to teaching. Any user can complete a site evaluation to provide us with information on how to make the site more effective, or can collaborate to improve the site by sending material to be posted.

The PPP site is located at http://www.ppp.uiuc.edu/. It can be viewed using either Netscape or Internet Explorer, with Java and Javascript enabled. Full use of the site also requires the installation of Macromedia’s Shockwave and Real Network's RealPlayer.

At the time that we began to think about putting together this web site, we had some experience with HTML and web page development. However, our level of web programming expertise  would not have allowed us to do much more than create a site that contained text, images, and hyperlinks. We knew that we wanted to include web-based Activities that would simulate a hands-on laboratory experience, but we lacked the skills to develop these on our own. We briefly considered hiring a web programmer, but we were not sure that we even knew enough to hire someone to accomplish what we wanted to do. After exploring several possibilities, we eventually decided to work with the Web Technology Group, a web development service on the University of Illinois campus. Web Tech is comprised of web design specialists, programmers with expertise in various aspects of web development, including HTML, Java, Flash, and streaming audio and video technologies, visual artists, and project managers. With this array of expertise available, we were allowed to create and implement some unique features for the site. Having Web Tech in charge of the programming also allowed us to focus on the design and specific content modules for the site. However, even with Web Tech to implement our ideas, the development of the site has consumed a considerable amount of our time. In addition to the time spent on content development, many hours have been devoted to testing and proofreading the material as it was added to the site.

would not have allowed us to do much more than create a site that contained text, images, and hyperlinks. We knew that we wanted to include web-based Activities that would simulate a hands-on laboratory experience, but we lacked the skills to develop these on our own. We briefly considered hiring a web programmer, but we were not sure that we even knew enough to hire someone to accomplish what we wanted to do. After exploring several possibilities, we eventually decided to work with the Web Technology Group, a web development service on the University of Illinois campus. Web Tech is comprised of web design specialists, programmers with expertise in various aspects of web development, including HTML, Java, Flash, and streaming audio and video technologies, visual artists, and project managers. With this array of expertise available, we were allowed to create and implement some unique features for the site. Having Web Tech in charge of the programming also allowed us to focus on the design and specific content modules for the site. However, even with Web Tech to implement our ideas, the development of the site has consumed a considerable amount of our time. In addition to the time spent on content development, many hours have been devoted to testing and proofreading the material as it was added to the site.

Initially, material on the  PPP site was presented in a very linear manner. Students were directed from one segment of information or one section of an activity to the next. In order to make the site more inquiry-based, this linear model was abandoned and a series of questions for students to explore was developed. Students can now access information in any pattern that they choose and can explore activities in either a guided or a user-directed manner. These changes have made the site an area of exploration, rather than one of programmed learning.

PPP site was presented in a very linear manner. Students were directed from one segment of information or one section of an activity to the next. In order to make the site more inquiry-based, this linear model was abandoned and a series of questions for students to explore was developed. Students can now access information in any pattern that they choose and can explore activities in either a guided or a user-directed manner. These changes have made the site an area of exploration, rather than one of programmed learning.

What do students think of the PPP site?

The PPP site has been evaluated by students in the University of Illinois Plant Pathology 100 class for the past six semesters. Detailed results of these surveys are available (Bruce et al., 2002).

We had many questions about the site and how it would be perceived and used by the students. We also wanted to be open to unanticipated reactions of students and to assessing our own experiences in the process. Our major evaluation questions were:

- How did students rate learning with the site in comparison with other modes of learning, such the classroom, lectures, labs, and textbook? More specifically, did they consider the online lectures to be interesting, informative, organized, and with the right amount of detail? Also, were the online lab activities easy to navigate, interesting, and informative? Did they allow thorough investigation of phenomena?

- What themes emerged in student comments about their experiences learning using the web? How did they perceive and use the web materials?

- What was our experience as developers? What did we learn about the development process?

We used web forms for the first two sets of questions. Each student completed evaluation forms on the Resources (formerly Lecture) and Activities (formerly Laboratory) sections, and an overall site evaluation. These forms asked users a variety of questions, some calling for Likert-scale responses and others inviting open-ended responses. We distinguished between the lectures and the labs because they call for different sorts of learning activities. Our central question overall was whether students viewed the site as better, worse, or the same as other modes of learning. We also wanted to know how they compared it to other course web sites and how they viewed specific aspects of it, such as the lectures and the labs.

For the basic questions, we performed separate t-tests with individual responses as the unit of analysis. We also calculated the percentage of positive responses. For both the lectures and the labs we also computed an analysis of variance looking at the effects of modules (Late Blight versus Dutch Elm Disease) and semester (across six semesters).

Students rated the web site as informative and better than other course web sites they had used. They saw the online lectures and laboratories as interesting, informative, and well organized. The labs also rated highly in ease of navigation and in providing students the opportunity to investigate phenomena. These findings are significant both educationally and statistically. They support the inference that the site design, despite problems noted by both students and instructors, was highly successful in meeting its goal of enhancing learning in the course.

In addition to the quantitative responses, students shared copious open-ended comments on different aspects of the site. Where the quantitative results essentially tell us that the students rated the site highly, the qualitative responses tell us how they perceived it, what use they made of it, and how they would like to see it improved. We analyzed their responses, first in terms of the questions as they were stated, and second, in terms of themes that emerged from repeated readings. Seven themes emerged from a detailed analysis of the comments:

- The web allows learner control of information access. This was usually seen as a good thing, but some saw the negative side that it's easier to skip around on the website and miss important ideas, whereas a lecturer can put clear emphasis on them.

- The web also provides greater learner control of pace and timing. Students can go at their own pace and review when needed in the web format.

- Having a website provides redundancy, which is generally, though not always valued. At a minimum, it provides a good supplement and a useful tool for studying.

- The web provides opportunities for inquiry, and should do more. It is a good way to explore phenomena in depth (lab activities).

- The personality of the instructor is hard to replicate. The website cannot replace a good lecturer who is excited about the material and adds humor and his/her own stories.

- Dialogue is crucial. The in-class lecture gives students a chance to ask questions and give input, where the web format does not. The current version of the site does provide greater means for dialogue, through bulletin board and email features, but would probably not satisfy many of the students who emphasized this point.

- Students learn through active engagement and articulation of experience. In the traditional lecture, many learn through the writing they do, even in the restricted medium of note-taking.

As we continued to develop the site, we learned from student reactions and from our own analysis. We increasingly saw the value in changing the site to become more supportive of an inquiry approach to teaching and learning. We thus began to modify the materials to allow various paths and modes of investigation, and to provide more dialogue and interaction features.

What is the future of the PPP site?

Our goal is to encourage broader use of the PPP site by both undergraduate students at other institutions and high school students. The site has been used by some students at other U.S. institutions, and has had thousands of “drop-in” visitors. We would like it to be used regularly by other instructors of plant pathology around the world.

Feedback from users will be critical in the future development of the site. We seek input to improve the design of the site, and to select the topics and design the activities for future modules. We would also like to link to the creative endeavors of other plant pathologists that will enhance the learning of students using the PPP site. For example, some pathologists have developed videos or animations that could be incorporated into or linked to from our site. These materials will enhance our site and will, in turn, be more widely used.

We encourage you to go to the PPP site, explore it, and send us your comments. Please send us your opinions on the most important topics we should add to the site. While we have lots of ideas, input from other plant pathology instructors will help us focus on what will be of the most use to the greatest number of plant pathology teachers and students around the world.

References

Benson, A.P. and B.C. Bruce. 2001. Using the web to promote inquiry and collaboration: a snapshot of the Inquiry Page’s development. Teaching Education 12:153-163.

Bruce, B.C., H. Dowd, D. Eastburn and C.J. D'Arcy. 2005. Plants, pathogens, and people: Extending the classroom to the web. Teachers College Record 107:1730-1753. (available at http://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentId=12094)

Burbules, N.C. and T.A. Callister. 2000. Universities in transition: the promise and the challenge of new technologies. Teachers College Record 102:271-293.

Eastburn, D.M. and C.J. D’Arcy. 1996. Late blight and the Irish potato famine. VHS video. 25 min. APS Press. ISBN 0-89054-169-8.

Eastburn, D.M., C.J. D’Arcy and L.A. McKee. 2000. Dutch elm disease and the American elm: the risks and benefits of monoculture. VHS video. 35 min. APS Press. ISBN 0-89054-250-3.

Rutherford, F.J. and A. Ahlgren. 1990. Science for all Americans. Oxford University Press. New York.

http://www.ppp.uiuc.edu/