Gray leaf spot, a foliar disease of corn (

Zeae mays) caused by the fungus

Cercospora zeae-maydis, has become of economic importance in many regions of the world over the past 10 years. Gray leaf spot was first described in the U.S.A. in 1925 on corn in Alexander County, IL. In the 1960s and 1970s, the disease became of concern in the eastern United States. As reduced tillage became more popular in the 1980s and 1990s, gray leaf spot became common in most of the corn growing areas of the midwestern and eastern United States. Today the disease can be found as far west as eastern Colorado, Kansas and Nebraska in corn fields under irrigation and north into Wisconsin and Minnesota. The disease has become distributed internationally being reported in Africa, Asia, and South and Central America.

YIELD LOSS:

Gray leaf spot must damage leaves at or just after silking growth stage to cause severe yield reduction. Early blighting of the leaves above the ear leaf leads to severe yield losses exceeding 50%. Blighting that does not occur until well into the grain fill period probably results in very little yield loss. Research has shown that there is not a direct relationship between the level of disease and yield loss. Several factors may contribute to this response, including yield potential of the hybrid, and the ability of leaf blighting to predispose hybrids to stalk rots. Premature stalk death and lodging is enhanced by severe leaf blighting.

EPIDEMIOLOGY:

An understanding of the epidemiology of gray leaf spot is helpful in explaining why the disease has increased in intensity, severity and distribution.

C. zeae-maydis overwinters in the debris of previously diseased corn plants remaining on the soil surface. In spring, conidia (spores) are produced and disseminated to corn plants by wind and rain splashing. They require several days of high relative humidity to successfully germinate and infect corn leaves. Several weeks may be needed for the development of mature lesions on leaves. Conidia for secondary spread are produced from two to four weeks after initial leaf infection. Tillage systems that leave sufficient previously diseased crop residue on the soil surface provide sufficient primary inoculum to produce severe levels of gray leaf spot.

INCREASE IN DISEASE PREVALENCE:

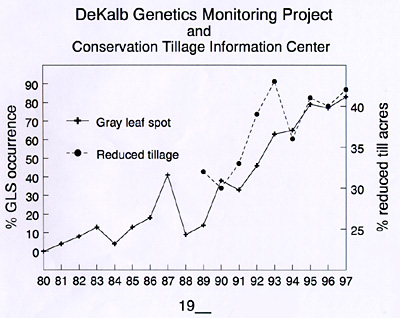

Dr. David R. Smith, and most recently Dr. Jim Perkins, of DeKalb Genetics Corporation have monitored the increase in disease prevalence since 1972 using plots at 24 locations throughout the corn growing regions of the United States. Data indicate that gray leaf spot prevalence has greatly increased during the last 20 years (Fig 1). The combination of the widespread use of conservation tillage, planting of susceptible hybrids and weather conditions that favor rapid spread of the disease in certain years have all attributed to the fact that gray leaf spot is now endemic in many regions of the world.

Figure 1. Occurrence (%) of gray leaf spot at 24 DEKALB Genetics Corporation corn pathogen monitoring project plot locations and percentage reduced tillage acres from the Conservation Tillage Information Center.

RISK AREAS:

In 1996, the North Central Regional Technical Committee identified those areas of the United States where gray leaf spot severity had been high enough to result in yield losses greater than 10% on high yielding susceptible hybrids (Figure 2). Yield losses in future years will depend upon environmental conditions and the overwintering of the fungus in crop residues. Yield losses also could occur in any area where the disease is present depending on environmental conditions and susceptibility of widely grown hybrids.

Figure 2. Gray leaf spot distribution as determined by members of the NCR-25 Technical Committee. Risk areas were identified based on reactions of susceptible hybrids, severity of past epidemics, the likelihood of favorable environmental conditions and use of conservation tillage.

THE FUNGUS:

Single-spore isolates of

C. zeae-maydis obtained from GLS lesions collected throughout corn-production regions of the U.S. yield cultures that exhibit subtle differences in growth rates and production of the phytotoxin, cercosporin, but they cannot be distinguished by standard and commonly used taxonomic criteria (e.g., characteristics and dimensions of conidia and conidiophores). Various molecular techniques (e.g., DNA fingerprinting) readily distinguish two groups that are significantly different from each other and from the sorghum pathogen,

C. sorghi. The most prevalent group is distributed throughout corn-production regions of the U.S. and the less prevalent group, is localized in the eastern third of the U.S. Isolates in this latter group tend to grow more slowly and produce much less cercosporin in culture. Both are pathogenic on corn, but differences in virulence (or infection phenotype) are not obvious. The isolates within each group are relatively uniform genetically. Thus, the potential for the existence or emergence of races or pathotypes of the pathogen is minimal.

GRAY LEAF SPOT MONITORING PROJECT:

In 1996 and 1997, the NCR-25 Technical Committee established a project to monitor the development of gray leaf spot across the corn growing regions of the United States, from Virginia to Nebraska. Results indicated that local populations of

C. zeae-maydis did not cause differential reactions on the 20 hybrids tested. These findings are significant because corn hybrids with resistance to local fungal populations will be resistant to gray leaf spot in other locations as well.

MANAGEMENT OF GRAY LEAF SPOT:

It is recommended that growers continue to use conservation tillage methods wherever practical. Growers should consider planting more different crops in rotation with corn in their farming system. A one or two year rotation away from corn would help reduce inoculum levels of

C. zeae-maydis. Growers should select the newer gray leaf spot resistant hybrids for use in fields where the potential for gray leaf spot is high. Selection should be based on yield potential and standability under gray leaf spot pressure. Fields should be monitored throughout the growing season for disease development and harvested early if high amounts of disease develop during grain fill. The economic benefit of controlling the disease with fungicides in grain production fields is still marginal except in high risk areas with significant yield losses each year.

SELECTED REFERENCES:

For information on gray leaf spot resistant germplasm see:

Coates, S. T. and White, D. G. 1994. Sources of resistance to gray leaf spot of corn. Plant Dis. 78:1153-1155.

For information on effect of crop residues on gray leaf spot see:

de Nazareno, N. R. X., Lipps, P. E. and Madden, L. V. 1993. Effect of levels of corn residue on epidemiology of gray leaf spot of corn in Ohio. Plant Dis. 77:67-70.

For pictures of different gray leaf spot lesion types see:

Freppon, J. T., Lipps, P. E., and Pratt, R. C. 1994. Characterization of the chlorotic lesion response by maize to Cercospora zeae-maydis. Plant Dis. 78:945-949.

For a general review of gray leaf spot see:

Latterell, F. M. and Rossi, A. E. 1983. Gray leaf spot of corn: a disease on the move. Plant Dis. 67:842-847.