INTRODUCTION

Cassava is an important food security crop in many tropical areas of the world. An organization called New Partnership for Africa’s Development has designated it as a crop of choice for poverty reduction in Africa. Cassava production in East African nations is under serious threat from two different diseases caused by viruses: cassava mosaic disease (CMD) and cassava brown streak disease (CBSD). Accurate diagnosis is vital for effective management of these diseases. The case study is intended to serve as an undergraduate-level teaching resource that acquaints students with diagnosis of CBSD (currently the most damaging of the two diseases), presents facts on the disease, and discusses principles related to its management.

This case study is a decision-making scenario in which Neema, a mother of eight children, who is a hard-working small-scale farmer in Soroti, Eastern Uganda (Figures

1A and

1B) and the chairlady of a self-help group, faces a food security crisis. This crisis erupts after she shared the CMD-resistant cassava varieties she was given by Opio, an agricultural project coordinator with a local non-governmental organization (NGO) called UWEZO, with her neighbors; soon, the tubers develop disease symptoms and begin to rot.

Figure 1A.Map of Uganda in Africa. |

Figure 1B.Map of Uganda showing location

of Soroti District. |

WHAT IS THE CRISIS?

The crisis is how to solve Neema’s and her neighbors’ problem and ensure they will have enough to eat. In addition, UWEZO hopes to be absolved from being blamed for distributing diseased cassava cuttings to growers. UWEZO obtained the cuttings from the cassava planting material multiplication center at the agricultural research center in Soroti.

OBJECTIVES

Demonstrate to students the challenges that growers face when trying to manage cassava virus diseases on their farms. This case study will:

- Introduce key facts about CBSD and its importance.

- Teach principles of CBSD pathology and management. (Students will realize that to develop an effective CBSD management strategy they need to understand how the disease develops and spreads from one farm to another).

- Explain how to diagnose CBSD in the field (challenges and constraints).

- Discuss the threat posed by CBSD to food security in the wider African Great Lakes region.

This case study will reinforce two fundamental plant pathology concepts: - Planting genetically uniform crops is risky.

- Plant pathogens are easily spread in vegetative propagation materials like cuttings.

THE CASE

View the Case Here

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Neema: A hard-working mother of eight children from Soroti Village in Eastern Uganda. She also is the current charilady of her women's self-help group.

Opolot: An 85-year-old widower who is Neema's neighbor. He visited his married daughter who lives several villages away and brought back a gift of cassava cuttings. A few roots were rotten when he collected them from his daughter at harvest time, and since then, most of his cassava has developed diseased roots.

UWEZO: (which means capacity in Swahili) is a local NGO that distributed cassava cuttings to the group in an effort to improve cassava production and food security in the area.

Mr. Opio: Agricultural project coordinator at UWEZO

Dr. Anne Adungosi: Extension officer in charge of root and tuber crops with the National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO), Soroti, Eastern Uganda

Lance: A study-abroad, third-year undergraduate biology student from a farm family in midwestern USA. He is on attachment with Dr. Adungosi at NARO.

Cassava: A woody shrub cultivated in the tropics for its starchy roots, and an important source of carbohydrates. Cassava plants are typically grown by planting cuttings (pieces of stem).

Key words/Acronyms: CMD, CBSD, NARO, NGO

Watch the Video About this Case Study

RESOURCES TO PREPARE STUDENTS FOR CLASS

Before the in-class session, students should read/view the introduction, the cast of characters, the case, and the following resources:

It is recommended that these materials be made available a lesson or two prior to the class and an electronic reminder to complete the pre-class work be sent shortly before the class. This ensures that students have adequate time to review the information and gain an understanding of CBSD transmission, symptoms, possible impact of the disease, and available management options. For instructors with no background in plant pathology, and/or cassava production, and/or farming systems in Africa, a

14-page background information bulletin on CBSD is recommended. The recording on cassava potential (cassava farming) would also assist such students to gain perspective and further appreciate the importance of CBSD in cassava production in the context of the case study.

ACTIVITIES FOR THE CASE STUDY

There could be two parts to the activity as time, location, and interest allow.

Part one: This is a classroom activity in which students will be divided into groups and assigned a perspective to support. The students will be given the case study and other CBSD reading materials beforehand. During the in-class activity, groups will review the case study and identify key information about CBSD (for example, how is the disease disseminated across regions and among farms? What symptoms are likely to be observed on infected tubers?). The students will then discuss each player in the case and their contribution to the problem, and then present this information to the rest of the class. Role playing is recommended as a presentation format.

Part two (optional): Students visit fields with CBSD-infected cassava plants at a local agricultural research station. Students gain first-hand experience on how to diagnose CBSD and discuss management options with the station staff.

After the small-group discussions, a group representative will give a brief presentation on their discussion and the talking points that arose to the rest of the class.

Role playing is recommended as a presentation format. During small group discussions, students will be expected to write out on chalk board/white board a minimum of two and a maximum of four, 140-letter-maximum “text/ tweet like” statements, comments, or questions they would give or have for Neema, Opolot, Mr. Opio, UWEZO or Dr. Adungosi on the issues. After each group has presented, each group will have an opportunity to respond to the issues/ allegations about their assigned character. The instructor will wrap up the exercise with pointers on international nature of science.

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

The case takes a real-world approach to highlight issues that arise when the impacts of plant disease threaten to become a natural disaster. The risk of using one variety (genetic uniformity), the dependence of growers on one crop (cassava), and the distribution of varieties from other places are familiar from many agricultural disasters to which

parallels can be drawn (e.g., the Irish potato famine of the 1840s). In addition, problems beyond food security are intertwined with disease management, including poverty reduction, economic productivity and human health implications; these should be considered.

This case study is recommended for students of field crop production, root and tuber crop production, IPM, plant health management, plant pathology, horticulture, or sustainable agriculture, where students can apply previously learned information. It is useful but not critical that students have a background and working understanding of plant disease cycles and IPM options available for disease management.

SUGGESTIONS ON HOW TO USE THIS CASE

The case study is designed for presentation in one 50 to 60 minute long class session, using a small group or whole class review and discussio style. The instructor serves as a moderator to maintain order and connect student ideas.

Information Review and Case Introduction:

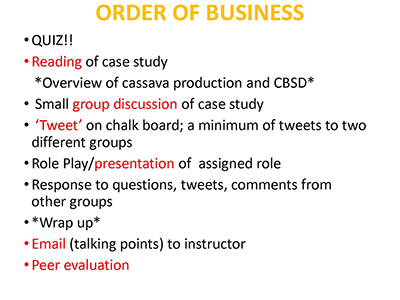

Students should be prepared to provide answers to 3-5 open ended review questions in 2-5 minutes at the beginning of class to demonstrate their understanding of the issues and key terms/concepts for this case (e.g., "tolerant varieties" and selection of planting material). A quick response system like clickers, index cards, or a show of hands can be used to get this feedback. A quiz could also be taken on this material before the in-class activity (

Figure 11). This information allows the insturctor to assess the students' comprehension of the background information and decide how much material to present during the introduction and review.

Figure. 11. Example in-class Agenda The instructor can begin by briefly (3-5 minutes) introducing the learning objectives and clearly explaining what will take place during the exercise. A brief overview of the keywords and the cast of characters is recommended (the level of detail is adjustable depending on how well prepared students are for the activity).

Activity:

After this introduction, students are divided into groups of 4-6.The groups are assigned to one of two possible teams. One team will focus on the perspective of Dr. Adungosi, who must develop talking points to explain the possible causes of the disease, why the situation has escalated and what farmers can do to mitigate the problem. The other teams focus on the perspective of Lance, the undergraduate American student on internship, and prepare possible talking points for an interview with journalists on the situation and how it has been handled. Depending on the size of the class, groups of students can be assigned to represent the other characters in the case. To start, students are allowed approximately 5 to 7 minutes for individual reading of the case. Then the teams of students spend 12 to 15 minutes discussing among themselves the problem facing Neema, Opolot and the members of the self-help group. They should think of possible questions that can be asked or observations that could be made to narrow down possible causes and management of the problem as well as to determine the potential impact of the problem on the characters. Groups should focus on preparing talking points depending on the perspective of the team to which they have been assigned. Students may search for additional information in the background document if they wish to. In our experience, some students enjoyed role-playing their assigned character; this helped to stress the critical nature of the CBSD problem.

Reccomendations:

During small group discussions students will be expected to write out on an electronic discussion board or chalk board/white board a minimum of three, 140-letter-maximum “text/ tweet like” statements, comments, or questions they would give or have for Neema, Opolot, Mr. Opio or Dr. Adungosi on the issues. This activity facilitates discussion by requiring concise, clear “tweets”; instructors should encourage students to distill and articulate their ideas and understanding. It is also an opportunity to provide additional information and highlight important issues and relevant points with the entire class.

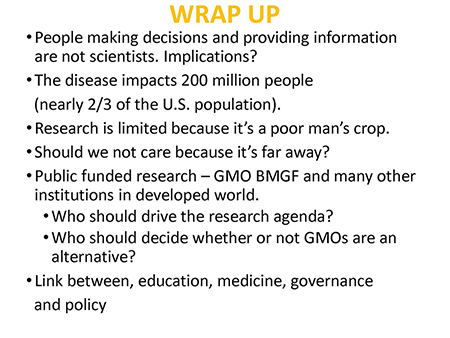

After the small-group discussions, a group representative will give a brief presentation on their discussion and the talking points that arose. Thereafter, students are encouraged to give their personal opinions on possible causes of disease spread, impacts of NGO crop production projects in communities and effective disease management to avoid food security threats (5 to 7 minutes). At the end of class the instructor gives a concise wrap-up (5 to 7 minutes) of the main points (Figure 12).

A handout is distributed regarding how Neema’s CBSD “education” could empower her to handle CBSD diagnosis in future.

Figure. 12. Example in-class wrap up agenda

The case was tested in four universities in Eastern Africa: Makerere University in Uganda, and University of Nairobi, Kenyatta University, and Chuka University in Kenya. Questionnaires and a show of hands were used both before and after the case was experienced in order to get feedback on time management, knowledge of content, and value of the case study approach to present the information. The introduction to the case at one of the institutions was time-consuming because it was a large class and the students had not gone over the material in advance. Students provided with the material beforehand had more meaningful discussions. The case made an impact even with students who were not familiar with the crop and disease after a solid introduction and watching the videos. The lecturer’s role was to moderate the discussion. With the larger classes it was valuable to have a team of teaching assistants and lecturers to help connect student ideas. More than 70% of the students appreciated the interactive nature of the teaching approach. Students in three out of four schools spontaneously role-played the characters in the case during the class presentations. Role playing was therefore incorporated as a suggestion for the group discussion section. Students reported that the case study approach enhanced their understanding of the CBSD problem better than a traditional teaching approach and said they would like to see more case studies in their classrooms.